I found 2017 taxing. It was a taxing year. I think it was for most people. Of course this isn’t a politics blog, so let’s not even go there, but even at the movies I did not find my usual escape. As often happens, it was late in the year before I found anything close to a list of favourites. But beyond that, just shutting out the stresses of the world has been harder, making sinking into a movie more mentally trying. It doesn’t help that I am noticing myself getting older, and staying awake through film after film is no longer a case of sheer willpower and enthusiasm. Oh for the days when two cups of well-timed coffee could get me through six features between bedtimes.

But at the same time, 2017 was actually somewhat of a landmark for cinema. After 2016’s #OscarsSoWhite scandal, who could have foreseen Moonlight take Best Picture over the charming but inferior La La Land, and in the way it did? Watching a livestream that was about a minute behind “live”, I could see panic and shock breaking out on my phone before anything had signalled La La Land was not the winner on TV. My Twitter feed was freaking out, and for a few moments I had to wonder what was about to unfold (a fainting filmmaker, a fight on stage?) – who’d have believed it? The shock has died down, but the Best Picture debacle of 2017 will go down as one of the greatest single moments in both film history and live television. What a time to be alive.

If 2016 had been a major year for Black cinema, 2017 shifted the focus to women. While it’s not a film I am especially in awe of, Wonder Woman hit with an undeniable impact, and moments like Gal Gadot strutting into No Man’s Land, or Chris Pine electing to be a handsome honeytrap to woo information from a female villain, completely rewrote the book on how Hollywood must view gender roles. (The huge success of the hilarious Girls Trip proved these changes were not solely going to benefit white women.) There’s more good work to do, but it feels exciting to be standing here while the sands are beginning to shift. And where representation behind and in front of the camera – and at the box office – showed extraordinary progress, an even bigger shift came as the rotten husk of Harvey Weinstein dominoed into his fellow abusers throughout Hollywood. Enough has been written by many greater talents about the #MeToo movement, but suffice to say the horror of hearing these stories come to light is regularly overcome by the swift victory of victims newly heard and perpetrators’ careers tumbling.

Before we get to the movies, let’s talk a little about what a year it was for TV. Since the dawn of True Detective and Black Mirror, TV has moved into EVENT territory, with individual seasons or episodes of far greater social (and artistic?) importance than tracking the fate of characters over too many years of one show. New shows like Legion, The Good Place, The Handmaid’s Tale, and American Gods stood out, but it was limited revivals that showed what TV could really do when focused artists expressed themselves through serialised storytelling – Twin Peaks: The Return and the belated final season of Samurai Jack (which oddly paralleled Peaks) truly stood out. David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, an astonishing metaphysical exploration of identity in 21st Century America through avant-fantasy and soap-operatic extremities, was such a remarkable achievement it triggered much fevered and pointless debate as to whether or not it was a “film”. The discussion is irrelevant, what matters is that it is. Purely to keep in check with previous years’ best-ofs, I have not included it on my list here, although with some reflection I wonder if it would have come out on top. I have subsequently seen the entire series on the big screen, and I can assure you, whether it’s a movie or not, it works as one.

Not a movie

Professionally 2017 was a good one – I began as Festival Manager of Doc Fortnight at MoMA, which had a tremendously successful year, and wrapped as a film consultant at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. I continued to write and edit at Cineaste (especially pleased with my broad review of Rebecca), while picking off some smaller projects. In my spare time, I continued a quest to watch every Palme d’Or movie, begun in 2016, and got up to the 2000s, so will finish that off this year. I also dedicated myself to watching one movie exceeding a four-hour runtime per month, which allowed me to pick off some exhausting cinematic must-sees, including Shoah, Out 1, Sátántangó, and Histoire(s) du cinéma. If I’m not going to make myself watch these things, no one else is going to!

On the big screen I saw some terrific rep screenings, from Don’t Look Now and Tokyo Drifter at Metrograph, Monterey Pop and Stalker at IFC Center, The Fireman’s Ball and Pelle the Conqueror at Film Forum, The Old Dark House, Hello, Dolly!, and Funeral Parade of Roses at Quad Cinema, and Strange Days, Husbands, and, err, Manos: The Hands of Fate at MoMA. Elsewhere, my home viewing ranged wildly from The Colour of Pomegranates to Arnold Schwarzenegger’s remake of Christmas in Connecticut. I have a range. Too much so.

As for the new releases of 2017, well there were many highlights and lowlights. I was left cold by Haneke’s Happy End, and thought the much-lauded A Ghost Story collapsed in the second act. The always-reliable Hirokazu Koreeda’s After the Storm hit me in the gut, but lacked the simple visual ambition of his better works. Okja did much the same for Bong Joon-ho, another favourite. The summer was riddled with flopbusters, but a few almost made my best of the year list, including Thor: Ragnarok, War for the Planet of the Apes, and Star Wars: The Last Jedi. Other close calls included Risk, The Big Sick, Personal Shopper, The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), Columbus, Dawson City: Frozen Time, and, until Phantom Thread dislodged it from the list-in-progress, Lady Macbeth. I’d have included the spectacular World of Tomorrow – Episode Two: The Burden of Other People’s Thoughts, except it’s a short, and then I’d have to defend putting a short on my best films list, and, well, you know.

Not a movie

Major releases I missed that might have featured include Coco, Song to Song, T2 Trainspotting, Raw, and I, Tonya, among many others. But as of early 2018, these are the 2017 films that have not left my mind…

20. Mudbound

There’s a well-trodden feel to Dee Rees’s racial melodrama, a sense that the toxic poverty and discrimination of the American South have been told before, and so well as to reduce further efforts to redundancy. And yet, here, through guiding a great ensemble, and with an exceptional rising cinematographer in Rachel Morrison at her side, Rees finds a balance between two complex family dramas, rebirthing the Mississippi landscape (Louisiana standing in) in remarkable, rich brown tones.

19. Molly’s Game

First-time director Aaron Sorkin brings his distinct writing style and energy to a one-of-a-kind story of a go-getting secretary-turned-underground-gambling-house-diva. Jessica Chastain brings her A-game, blasting out Sorkin’s buzzy dialogue, with plenty of fun sparring partners (Idris Elba is terrific as her attorney, following her bust by the Feds). It keeps character the focus, without letting the poker overcomplicate the drama. The final act devolves briefly into nonsense, but it’s not enough to slow it down. The screenwriter-auteur seems to understand the collaboration great cinema requires, and smart editing and handsome cinematography make this a memorable debut.

18. A Quiet Passion

The inimitable Terence Davies made his first (and only?) misstep with 1995’s The Neon Bible, a Georgia-set period piece that felt outside the range of his very British working class viewpoint. Having honed himself as a master of period tone in the decades since, Davies’s second American tale reveals the depth of his maturity as an artist. With beautiful imagery matched by splendid pacing and often caustic wit, the lives of poet Emily Dickinson and her family are realised thoroughly. If it at times ventures away from the historical truth, it does so only to keep things lively, and Cynthia Nixon is the cornerstone of a terrific cast.

17. Nocturama

One of 2017’s boldest pictures, French filmmaker Bertrand Bonello’s anarcho-thriller Nocturama is a Parisian-set genre smorgasbord. Beginning as a heist movie, in which a gaggle of misaffiliated teens sets off a series of bombs in order to topple the economic status quo, it shifts to satire, bordering on farce, as the young antiheroes hide out in an abandoned ultra-bougie department store. It ends in horror. The first act shows the deftest filmmaking, as Bonello intercuts between his characters at various points in the timeline, but the lengthy central act unveils a bolus of social commentary as the youths interact, often joyfully, with the elaborate trinkets of a society they profess to despise.

16. The Shape of Water

There are few visualisers of the fantastic working in Hollywood today with the skills of Guillermo del Toro, but his screenplays (especially the English ones) rarely match his remarkable imagery, with strained dialogue and comically heavy-handed metaphors. But here, working with Vanessa Taylor (whose major credits include a handful of Game of Thrones episodes and a Meryl Streep romcom), he has produced his best work since Pan’s Labyrinth. A complex character study, loaded with wit, and a truly out-there love story borrowing from 1950s B-movies and Beauty and the Beast, The Shape of Water shows tireless craft (amazing, rust-encrusted sets, plays with light, splendid music), and is held aloft by the quality of its performances, particularly Sally Hawkins as a mute janitor at a government research lab who rescues, and falls for, a South American fish-man creature. Michael Shannon’s villain is as under-baked as all of del Toro’s villains (although the actor, as always, acquits himself admirably), but otherwise the writing is stellar, and builds to a beautifully realised finale.

15. Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri

Martin McDonagh has always revelled in being an outsider – his most famous works, plays set in the West of Ireland, derived from his visiting his extended family as a youth, observing the peculiar and exciting linguistic flourishes that he magnificently retooled into hilarious, mean-spirited tales like The Beauty Queen of Leenane. Here he has bitten off more than he can fully masticate, with a Midwestern setting that he is perhaps too much removed from to fully capture. But what he’s done remains an exceptional entertainment, darkly imagining the war of printed words between a bereaved mother and a well-intentioned sheriff, who she holds responsible for the failure to capture the brutal killers of her daughter. The characters and situations are larger-than-life, with performances (Frances McDormand, Woody Harrelson, and Sam Rockwell especially) to match. Its contemplation of redemption for racist, Red State caricatures feels ill-timed in an angry, polarised America, but the strength of the dialogue and the crisp texture of Ben Davis’s cinematography make it a film difficult to deny in its quality.

14. Marjorie Prime

Yes, yes, yes, it’s just a play I hear you say, but when a play is this good, when it’s this well-written, this cogent and timely in the issues it addresses, the medium feels irrelevant. Adapted from Jordan Harrison’s stage drama with minimal flourish by Michael Almereyda, Marjorie Prime looks at a near-future where the grieving process is aided by memory uploads of the departed, appearing as interactive holograms of them at whatever age the customer chooses. Too introspective and quietly sad to be a Black Mirror instalment, it’s a heart-rending look at memory and regret, acted superbly by its four stars, Lois Smith, Jon Hamm, Geena Davis, and Tim Robbins.

13. Your Name

A record-smashing success both at home in Japan and around the world, writer/director Makota Shinkai’s Your Name is a romantic fantasy comedy that pushes in every direction – a huge emotional impact; shocking supernatural twists; big, silly laughs – while even challenging the likes of Studio Ghibli in the quality and richness of its animation and colours. Billed as a teen body swap tale, initial gender gags give way to a deeply satisfying romance and ethereal revelations. If the many subplots seem tired or convoluted, they all wash away in the image of two star-crossed lovers meeting for the first time across the flare of a setting sun.

12. Dunkirk

The sort of cinematic grandeur that Hollywood has forgotten in the wake of CGI city explosions, Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk is simultaneously experimental and defiantly old-school. Recreating the famous naval escape of WWII in breath-taking 65mm IMAX, Nolan’s film is a triptych edited out of sync, revealing days on the beach, an afternoon on the sea, and one terrifying hour in the air. Hans Zimmer’s thrilling score ticks with intensity as time runs out for the soldiers. The pressure builds in all three stories as they meet at the day’s end, culminating in a cathartic welcome home, accompanied by Churchill’s most famous address. This is the war movie at its most ambitious, even if the characters’ screentime is too diluted to ever truly feel in the thick of it with any of them.

11. The Florida Project

Following his impressive Tangerine, a film famously shot entirely on an iPhone, Sean Baker’s Florida Project is mostly crisp, bumblegummy 35mm. An affecting look at childhood in poverty, and a savage critique of the selfie generation’s self-absorption being anathema to parenthood, this is a minor triumph of humanism, with Brooklynn Prince and Willem Dafoe as neighbours, decades apart in age, neither of whom allow the minor tragedies of daily living scuttle their enthusiasm or hopefulness. A finale that dips into magical realism both looks and feels out of place, but it barely leaves a dent in this dramatic and regularly hilarious work.

10. Blade Runner 2049

Few were more sceptical than me at the idea of a new Blade Runner sequel/reboot/anything. But on the heels of the splendid Arrival, Denis Villeneuve had more than proven his sci-fi chops. What we got was a shocking success, building on the mythology of the Philip K. Dick universe, while somehow reinforcing the mystery around Rick Deckard’s humanity, questioned at the close of Ridley Scott’s original, leaving it satisfyingly unanswered. The exquisite production design and imagining of future technology that both aids and alienates made it a new dystopia, not a rehash. The cast, from Harrison Ford and Ryan Gosling, to exceptional supporters Robin Wright, Ana de Armas, and Sylvia Hoeks, brought more than could be expected to a thought-provoking, largely action-free sci-fi gem.

9. Get Out

If any film could vie with Wonder Woman for the title of “most important film” of 2017, it was Get Out. The icing on the cake is what an incredible achievement Get Out is, even before its socio-political satire and revelations are taken into account. The tale of a young African-American man lured into the welcoming abode of an over-eager white family who, secretly, don’t so much want to kill him as be him, latches on to numerous under-spoken-of issues bubbling beneath the surface of post-Obama culture. First-time director Jordan Peele impresses hugely from the get-go, but its his script that dominates, fluctuating with ease between social commentary, brilliant black comedy, and nightmarish horror; apparent throwaway lines of dialogue early on whip back as ingenious foreshadowing of gags and grotesqueries. Star Daniel Kaluuya offers a performance that horror cinema hasn’t seen the likes of in a generation.

8. The Killing of a Sacred Deer

Yorgos Lanthimos continues to revel in his highly personalised brand of faithlessness in humanity, and the results remain inspired. Here suburban inanity is punctured by Barry Keoghan’s intrusive oddball Martin, who forces himself into a pretentiously happy family’s home life, blaming the patriarch, a doctor, for the death of his own father. Lanthimosian performances are emotionally wooden as always, played with bitter somnambulism by Colin Farrell and Nicole Kidman. The moral dilemma at its core is played as a cunning, tormented thought experiment, shifting the movie suddenly from darkly comic to spine-cringingly horrific.

7. Lady Bird

On the surface a semi-autobiographical coming-of-age drama from first-time director Greta Gerwig, Lady Bird is encased in a study of daughters and mothers, and the generational misunderstandings that can blind loved ones to others’ needs. Saoirse Ronan and Laurie Metcalf merge with their characters – the shared frustration with one another is written in every movement of their faces. Unshowy production design keeps the story grounded, while Gerwig’s script and the exceptional editing of Nick Houy make the film as unforgettable as the drama.

6. BPM (Beats Per Minute)

As the AIDS crisis has diminished in the West, it can be hard for some to remember the terror it incited in the early ’90s. In my youth it seemed the greatest threat to humanity in a pre-9/11 world. But for those who feared it, nothing could compare to the experiences of those who lived with it, unsupported, unheard, uncared for. Robin Campillo’s award-winning BPM is a sensational dive into the world of French AIDS activists 25 years ago, gently and caringly listening to their stories and hopes and fears in intimate love scenes, while also making clear the incredible work and organisation done by ACT UP in fighting for the rights and humanity of those living with HIV/AIDS. The acting and writing capture a unique energy with exceptional passion, while the film features perhaps the most outstanding scene transition of the year, as specks of dust caught in the wavering lights of a nightclub morph into human cells, under attack from within.

5. The Teacher

One of the most overlooked films of 2017, Jan Hřebejk’s The Teacher is one of the finest works studying abuses of power in recent memory. Borrowing a concept from 12 Angry Men, it is set at a PTA meeting called to question the future of school teacher Mária Drazdechová, in the closing decade of communist Czechoslovakia. Drazdechová is accused of using her position of authority within the Party to manipulate parents into doing copious favours for her, and bullying her students so severely that one even attempts suicide. Using flashbacks to show their interactions with Drazdechová, while intercutting children and parents to reveal generational (dis)similarities, one by one the parents are convinced to come forward. It’s an astonishing piece of storytelling, and in the title role Zuzana Mauréry dominates the screen, making her one of the most memorable villains of the 21st Century so far.

4. Faces Places

As she approaches 90, but appears to come nowhere near to slowing down, Agnès Varda once again hits the road to traverse France and find the most interesting people she can interview and shoot. Her companion/co-director/partner in crime is 30-something graffiti artist JR, whose portrait photography is blown up to enormous sizes and plastered in the most aesthetically pleasing and surprising places. As Varda’s eyesight fades, the trip and film become a metaphor for what might be her last chance to truly see the world and its people. What begins as a sweet, charming journey, documenting the towns and faces Varda and JR come across, expands into something far greater, about lives lived and not lived, as the duo attempt to confront Varda’s past with two towering male legends of French cinema, her late husband Jacques Demy, and long-time friend turned hermitic curmudgeon Jean-Luc Godard. At her impressive age, Varda continues to push the boundaries of the documentary arts, never losing hope or faith in the real, human magic of the world around her.

3. Phantom Thread

Paul Thomas Anderson has never made a bad film, but his best work always comes with narrow focus; direct character studies rather than sprawling, Altmanesque ensembles. Phantom Thread is his smallest film since Punch-Drunk Love, and features barely more than three characters: fashion designer Reynolds Woodcock, his young muse Alma, and his commanding sister Cyril. What begins as a straightforward melodrama about a woman unable to crack the eccentric brilliance of her much older lover – echoes of Rebecca abound – morphs into a stranger, sexlessly kinkier story about emotional domination. It looks luscious, while Jonny Greenwood’s score is as seductively brilliant as Daniel Day-Lewis’s Woodcock. Vicky Krieps is strong as Alma, but much of the film is stolen by Lesley Manville’s divinely snarky Cyril.

2. Call Me By Your Name

Luca Guadagnino undoubtedly had a masterpiece in him, but it wasn’t clear it would come so soon. His fifth fiction feature, adapted from André Aciman’s novel by the iconic James Ivory, is a quiet and powerful love story set in Northern Italy. Elio, aged 17, meets Oliver, 10 years his senior, his father’s assistant in excavating artefacts from Roman antiquity. What begins as a resistant friendship between two men whose only common trait is a shared Jewish ancestry, erupts into romance through a succession of spoken and unspoken moments – glances of the eyes and the hand against skin. Superbly paced to create the feel of a summer spent falling in love, the story beats with the pain and beauty of first love. Shot in extraordinary sunswept frames by Uncle Boonmee’s Sayombhu Mukdeeprom and accompanied by the delicate bombast of Sufjan Stevens’s music, it is never less than gorgeous. Lead actors Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer offer up their impressive bests, but it is Michael Stuhlbarg as Elio’s calmly caring father who leaves the most powerful mark, connecting one boy’s heartbreak to a legacy of unexpressed emotion.

1. The Square

No movie in 2017 dared to tackle as many issues as Ruben Östlund’s The Square, and few movies have ever aimed for so many targets without spreading themselves thin. Whereas his breakout 2014 darling Force Majeure focused squarely on fragile masculinity, The Square encircles that issue in addition to commentaries on homelessness, the immigrant crisis, the incompatibility of art and commerce, the Americanisation of Europe, and casual sex. It is a ruthless satire on the art world that sees Claes Bang’s curator Christian struggling with the titular artwork, which professes to be a sanctuary in which all are equal. But none are truly equal within or without, as power shifts from person to person, from Christian to the thief of his smartphone to the vengeful child inadvertently accused of the crime. A self-revolved artist is overcome by a peer who has turned to animalistic performance, and bourgeois society is at first delighted and almost instantaneously outraged. Christian, perceiving himself a demi-celebrity, argues with a woman he has slept with who won’t let him dispose of the condom they have used himself, convinced she is out to steal his sperm, in surely the year’s most hysterical scene of awkward comedy. The film has so much to say about 21st Century living, and our inability to comprehend much or all of it. It is ruthless and hilarious, ceaselessly entertaining, and a consistently startling work of cinema, pristinely shot, tremendously executed.

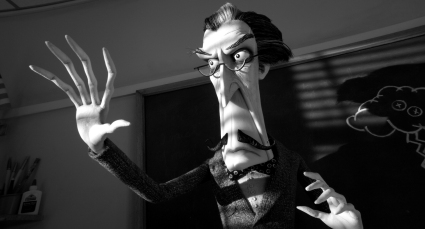

An artist’s interpretation of me telling you how good The Square is

————————————————–

Oh, and of course, there’s the worst movies. These were works from 2017 that either bored me beyond redemption, entertained me in ways they were never meant to, or left me simply stupefied by their outrageous, unearned out-there-ness. I didn’t see The Emoji Movie, while Justice League was too run-of-the-mill to even bother feeling negative towards, and Transformers: The Last Knight gave us the gift of Cogman, without whom it would surely have made this list.

5. Ghost in the Shell

Narrowly beating Death Note for the misguided anime remake of 2017, Ghost in the Shell brought nothing new to the table, and in keeping a Japanese setting placed a target on its chest for accusations of white-washing. Audiences and critics justifiably struck. Borrowing all its finest images from the source material, its mot inventive creation was to have the Caucasian hero and villain be secret Asian people. In what feels like a lazy Saturday Night Live sketch, characters repeatedly pause to use the terms “ghost” and “shell”, which mean, in this context, as they make very, very clear, “soul”… and “body”. It is agony.

4. Lemon

Another study of an anxious intellectual struggling with the emotional and career success of those around him, Lemon is a mean-spirited, aimless film, relying too much on the muted charisma of its stars. The story reaches no conclusions (nor a reason for there to be no conclusion), while the blown-out yellowed palette exhausts after the first few minutes. There’s much talent here, but all of it is misdirected.

3. The Book of Henry

Behold a child smarter than his mother! Cringe when you should be weeping as he dies suddenly of a brain tumour! Thrill as his mother follows his instructions from beyond the grave to murder their neighbour who is abusing his daughter! Gasp as that abuse is made clear through interpretive dance! That rare example of a movie that simply should not exist.

2. The Mummy

Universal’s self-immolating attempt to create a shared “Dark Universe” of their famous monster characters began (and ended?) with this dour-looking action film which follows Tom Cruise’s uncomfortably quippy hero from the Middle East to London, pursued by a sexy zombie and her army of unspectacular CGI. Tonally scattershot, impossibly dull, mercilessly sequel-thirsty.

1. Baywatch

The lowest point of ironic media repurposing, this painfully unfunny comedy has the audacity to tease a television show that showed more impressive cinematic craft in its opening credits montage than this can in two hours. Smothering the natural charisma of stars Dwayne Johnson and Zac Efron, this bounces from comic set piece to comic set piece with awkward scene transitions and a threadbare drug-smuggler plot failing to hold it together. An extended scene in which Efron’s character must fondle the genitals of a corpse feels like the perfect metaphor for this film: ugly, gross, determined to insult, but just cold and flaccid.